The excitement of vintage seemed like only yesterday. But this week, the first of our 2018 wines was bottled! Here are the first boxes of our Somerled 2018 Sauvignon Blanc hot off the bottling line!

The excitement of vintage seemed like only yesterday. But this week, the first of our 2018 wines was bottled! Here are the first boxes of our Somerled 2018 Sauvignon Blanc hot off the bottling line!

The wine finished cold stability early last week and was filtered. Rob did a final tasting at Lodestone during last week and decided it didn’t need any further additions or movement. At that point, the tank was relocated into a temperature-controlled room to help bring it up to a good bottling temperature (around 15C). Monday it was loaded onto the truck and off it went to Boutique Bottlers at Stockwell in the Barossa. Rob and his brother-in-law Wal (you can just call him Uncle Wal!) were there to see it go into bottle yesterday.

In Rob’s words, “It’s a lovely pale, bright wine with a really lifted floral/perfumed nose and a delicate dry soft clean crisp palate. Perfect aperitif!!” I think that means he’s happy!

Want to know a bit more about this popular, but sometimes unappreciated variety?

Sauvignon Blanc originated in the Loire Valley and Bordeaux regions in France. The name literally translates to “Wild White”. Sauvignon Blanc is also famous for parenting the noble grape, Cabernet Sauvignon, also from Bordeaux.

Sauvignon Blanc is a very flexible variety – it can be grown in a number of different climates, resulting in a range of styles. In Bordeaux’s maritime climate, Sauvignon Blanc produces wines with ripe full fruit flavour. While in the continental climate of the Loire Valley in western France, make wines of purity, minerality and length. In the Sauternes region of Bordeaux in south-west France, when blended with Semillon and aided by the Botrytis fungus, some of the world’s greatest sweet “dessert” style wines are produced.

The Marlborough region in New Zealand is probably one of the most well-known producers of Sauvignon Blanc these days, but we Aussies make some pretty good ones too (and not just of the Somerled variety!).

Aussie Sauvvie

As I’ve mentioned, Sauvignon Blanc differs greatly depending on the climate and soil in which the grapes are grown. Australian Sauvignon Blanc runs the gamut of flavour from herbal, grassy, sour citrus and gooseberry, to passionfruit and tropical fruit characters. Structurally these wines can be light in body and crisp or medium-bodied and rich. Some, like our Somerled Fume Blanc, are oaked to add a further dimension of complexity. Sauvignon Blanc is Australia’s top selling white wine in dollar terms.

Which region in Australia produces the best Sauvignon Blanc?

Well, of course, I’m going to say the Adelaide Hills! But, the truth is, they are all so different it would be unfair to compare them. Let’s take a closer look at each regions and the styles of Sauvignon Blanc they produce…

South Australia

While we share the same “cool climate” categorisation, the Adelaide Hills is slightly warmer than Marlborough. It is for this reason that we produce crisp, fresh Sauvignon Blanc with tropical flavours rather than the trademark grassy notes of our NZ counterparts. Coonawarra also produces some lovely cool climate Sauvignon Blancs

South Australia also produce some richer, riper examples in McLaren Vale and Langhorne Creek. These aren’t as popular here because we’re not used to this rich style in Australia.

Western Australia

Margaret River Sauvignon Blanc has ripe, zippy and grassy flavours that have attractive, tropical musky-asparagus aromas. Pemberton is a small Western Australian region that produces distinct Sauvignon Blanc styles with tropical fruit aromas and flavours.

Victoria

Victoria’s cool regions produce some fresh and vibrant Sauvignon Blancs, with those from the Yarra being typically elegant and restrained. King Valley and Goulburn Valley Sauvignon Blanc is often grassy and also shows classic cool-climate freshness and vibrancy.

Tasmania

The cool Tasmanian climate is ideal for Sauvignon Blanc, that typically has high levels of crisp acidity, which gives the wine great freshness.

Orange, NSW

A relative newcomer – Orange’s cool climate and high altitude have proved to be ideal conditions for creating Sauvignon Blanc with fresh, herbaceous characters.

How does Rob make his Sauvignon Blanc so “mouth-watering”?

The secret to Rob’s amazing Sauvignon Blanc is that he likes to pick the fruit nice and early. That way, the soft acid or what he likes to call “mouth-watering” acid, is still present. The longer the fruit is left on the vine, the more it ripens – replacing the acid with sugar. If Rob picked it later, then he would need to add acid in the winery to create the same effect.

Rob also like to choose fruit from different parts of the vineyard to get a nice range of flavours. From ripe mango in the full sun areas to zingy passionfruit in the cooler, shadier morning sun rows.

The overall effect is a soft, mouth-watering, elegant Sauvignon Blanc!

If you’re a Jockey Club member, watch out for a bottle of this new release in an upcoming pack… it won’t be too far away. Once it has been released to the club you will be able to taste it at the cellar bar – why not pop in for a side by side comparison with the 2017 version?! (and a platter and another glass or two…!)

Thank you! … you know who you are.

A huge thank you to everyone who contributed to last week’s post with your great questions and feedback! Make sure you keep an eye on the blog for a post dedicated to your topic of interest.

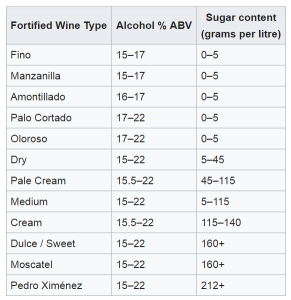

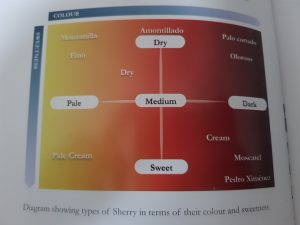

Another unique feature in the production of apera is the use of a solera system. Barrels of wine are arranged in a pyramid-like stack with the youngest wine in the top layer and the oldest wine in the bottom layer. At bottling time, the wine to be bottled is removed from barrels in the bottom layer of the solera, taking only a small portion. Then each cask is refreshed from the layer above. This results in a progressive mixing of young wine with older wine, a process known as ‘refreshing the wine’.

Another unique feature in the production of apera is the use of a solera system. Barrels of wine are arranged in a pyramid-like stack with the youngest wine in the top layer and the oldest wine in the bottom layer. At bottling time, the wine to be bottled is removed from barrels in the bottom layer of the solera, taking only a small portion. Then each cask is refreshed from the layer above. This results in a progressive mixing of young wine with older wine, a process known as ‘refreshing the wine’.

“So, I could immediately see a great future for our Somerled apera as a wine modelled on the Spanish Palo Cortado style – and that’s the way it’s going. It’s now over 9 years old, and has been in barrel for nearly all that time. The flor yeast film has long disappeared, but the flor influence is still there, just as it is in the old Spanish Palo Cortados. It has deepened further in colour, so that it has a lovely golden tint with a touch of the tawny, and the aromas and flavours are incredibly lifted.

“So, I could immediately see a great future for our Somerled apera as a wine modelled on the Spanish Palo Cortado style – and that’s the way it’s going. It’s now over 9 years old, and has been in barrel for nearly all that time. The flor yeast film has long disappeared, but the flor influence is still there, just as it is in the old Spanish Palo Cortados. It has deepened further in colour, so that it has a lovely golden tint with a touch of the tawny, and the aromas and flavours are incredibly lifted.  After the success of our latest Harvest Day last weekend I thought it was about time we took a closer look at our lesser-known variety.

After the success of our latest Harvest Day last weekend I thought it was about time we took a closer look at our lesser-known variety. The highly serrated nature of its leaves makes it one of the most recognisable varieties in the vineyard. It is one of the few varieties where the leaves turn bright red in autumn. It’s one of the most beautiful sights!

The highly serrated nature of its leaves makes it one of the most recognisable varieties in the vineyard. It is one of the few varieties where the leaves turn bright red in autumn. It’s one of the most beautiful sights! Regional matches provide a template for us to understand more about what’s going on structurally with wine & food pairings. They’re not always perfect, but they’re often a great place to start.

Regional matches provide a template for us to understand more about what’s going on structurally with wine & food pairings. They’re not always perfect, but they’re often a great place to start.

Remember that place we got all the grapes from?

Remember that place we got all the grapes from? The difference between cane and spur pruning is best explained by this diagram.

The difference between cane and spur pruning is best explained by this diagram.

Without going into too much detail there are a number of instruments which can be used to take this measurement. If you are lucky enough to work in a laboratory which has a digital refractometer, then life is easy. Smaller wineries though rely on a piece of equipment called a hydrometer.

Without going into too much detail there are a number of instruments which can be used to take this measurement. If you are lucky enough to work in a laboratory which has a digital refractometer, then life is easy. Smaller wineries though rely on a piece of equipment called a hydrometer. A hydrometer is usually made of glass, and consists of a cylindrical stem and a bulb weighted with mercury or lead to make it float upright. The juice or wine is poured into a graduated cylinder, and the hydrometer is gently lowered into the liquid until it floats freely. Hydrometers have a scale inside the stem, so that the person using it can read the Baume measurement.

A hydrometer is usually made of glass, and consists of a cylindrical stem and a bulb weighted with mercury or lead to make it float upright. The juice or wine is poured into a graduated cylinder, and the hydrometer is gently lowered into the liquid until it floats freely. Hydrometers have a scale inside the stem, so that the person using it can read the Baume measurement. It’s a very delicate process, one which needs constant monitoring to ensure the levels are optimum. In the laboratory, pH is measured using a pH meter.

It’s a very delicate process, one which needs constant monitoring to ensure the levels are optimum. In the laboratory, pH is measured using a pH meter. I know. I’m so sorry… I promise that will be the last pun!

I know. I’m so sorry… I promise that will be the last pun! The Sauvignon Blanc is going through the

The Sauvignon Blanc is going through the