This week we take a look at what happens inside the winery laboratory!

OK, “fun” might be a bit of a stretch, but for a science geek like me, it is!

Over the course of the last few months, as I have led you through some of the key steps of making wine, I have alluded to this placed called the “laboratory”. If you’re imagining a corner of the winery where geeky, glasses-and-white-lab-coat-wearing people spend their days playing with beakers and test tubes, well….. actually, you’d be pretty much spot on. However, if science (or learning about it) is your thing, it is one of the most exciting and fascinating places in the winery.

It is also one of the most important. The winemaker relies on data from “the lab” (that’s what all the cool kids call it!) to make key decisions during the winemaking process. What many people don’t understand is that winemaking is highly scientific. That’s where Rob, and his background as a (maths and) science teacher, comes in very handy and probably why he is so good at it. He understands the importance of getting things right.

So what happens in this place of wonder and awe?

There are a number of tests that the laboratory can perform during the lifespan of a wine… from pre-harvest of the grapes to bottling of the finished wine.

Let’s take a closer look at a few of the key tests…

Measurement of residual sugar

By now, you should be getting pretty familiar with this. Previously we’ve talked about measuring Baumé in grape juice to determine when the grapes are ready to pick. We’ve also looked at how the same measurement is used to determine whether the ferment is progressing and when it has finished. Considering this measurement is taken a few times before harvesting the grapes and then usually twice a day during fermentation, it’s easy to see that this is one of the most basic but important tools a winemaker has.

Without going into too much detail there are a number of instruments which can be used to take this measurement. If you are lucky enough to work in a laboratory which has a digital refractometer, then life is easy. Smaller wineries though rely on a piece of equipment called a hydrometer.

Without going into too much detail there are a number of instruments which can be used to take this measurement. If you are lucky enough to work in a laboratory which has a digital refractometer, then life is easy. Smaller wineries though rely on a piece of equipment called a hydrometer.

A hydrometer is usually made of glass, and consists of a cylindrical stem and a bulb weighted with mercury or lead to make it float upright. The juice or wine is poured into a graduated cylinder, and the hydrometer is gently lowered into the liquid until it floats freely. Hydrometers have a scale inside the stem, so that the person using it can read the Baume measurement.

Measurement of pH

If you can think back to your high school science days, you may remember a term called pH. It’s a tricky concept to grasp, but basically, it is a measure of acid in a liquid. Acids exist in different forms, and one of these forms is free hydrogen ions. pH measures the concentration of hydrogen ions, which are important in that they influence chemical reactions in the juice or wine. Concentrations of these ions in solutions are very low, so chemists invented a scale for expressing acid condition in all sorts of liquids (not just wine). This scale ranges from 0 – 14. Pure water is neutral at pH 7, lemon juice sits around pH 2 and grape juice and wine usually sits in the range of pH 3 – 4.

The thing to remember about pH in wine is that the higher the pH, the greater chance of oxidation. During the winemaking process, some of these free ions are used up through chemical reaction so the pH increases. Acid additions are often made with the aim of achieving an acid level which is in balance with the sugar, alcohol and fruit in any particular wine.

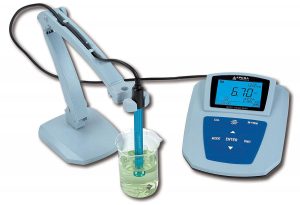

It’s a very delicate process, one which needs constant monitoring to ensure the levels are optimum. In the laboratory, pH is measured using a pH meter.

It’s a very delicate process, one which needs constant monitoring to ensure the levels are optimum. In the laboratory, pH is measured using a pH meter.

Testing sulphur dioxide levels

As we discussed a couple of weeks ago, the production and addition of sulphur dioxide is an important element in the process of making wine. It is also important to make sure the level of sulphur in the wine is just enough to help prevent oxidation, and at the same time keeping the level as low as possible.

This is a pretty involved test. I have included the below video for those of you who are interested. But be warned… it is of the educational, not entertaining variety. I won’t be offended if you don’t press play!

I could go on…

… and on, but I won’t (for now)! I’ll stop before I lose you all, but I may come back to the lab every now and then to chat about other important tests (unless I get a resounding “no! please don’t!” from you all in the comments section).

If you are particularly interested in this side of wine-making, please let me know via the comments. I’m happy to answer any questions you may have.

I know. I’m so sorry… I promise that will be the last pun!

I know. I’m so sorry… I promise that will be the last pun! The Sauvignon Blanc is going through the

The Sauvignon Blanc is going through the

The Baumé was lowish (11.2) and that is exactly how Rob wants it. The juice is perfect with lovely aromas and flavours, and such an attractive green tint. All up 3000 litres of juice came out of the grapes. This will be used for both the 2018 Somerled Sauvignon Blanc and the Fumé Blanc (in quantities yet to be determined by the winemaker!).

The Baumé was lowish (11.2) and that is exactly how Rob wants it. The juice is perfect with lovely aromas and flavours, and such an attractive green tint. All up 3000 litres of juice came out of the grapes. This will be used for both the 2018 Somerled Sauvignon Blanc and the Fumé Blanc (in quantities yet to be determined by the winemaker!).