Ok, I am going to say it once, and then you have to pretend you never heard it.

Sherry

… or Apera, as we must call it in Australia these days. Thanks to a trade agreement between Europe and Australia back in 2010, local fortified winemakers were banned from using the ‘S’ word.

Why?

Sherry is a fortified wine made from white grapes grown near the town of Jerez, in Andalusia, Spain. What you may not know though is the name ‘Sherry’ is actually an anglicization of ‘Jerez’. So, we can’t call it that for the same reason we can’t call Australian sparkling wine ‘Champagne’.

Wine Australia maintains the Register of Geographical Indications and Other Terms to ensure correct use of Geographical Indications (GIs) and Traditional Expressions (TEs) on both wine labels and associated advertising material in Australia. There are over a thousand protected European names.

Anything which is protected can not appear in the presentation and description of a wine that isn’t connected to it in any context. There is a clause in the Act which also prohibits the use of terms like ‘style’, ‘method’ or ‘imitation’.

For further details and a full list visit the Wine Australia website here.

A 2010 trade agreement, you say? Why am I only hearing about this now?

That’s a good question! My guess is that it is simply not very popular. When we think about Sh… sorry, apera, we often remember it as something our grandparents drank (ie. not cool!).

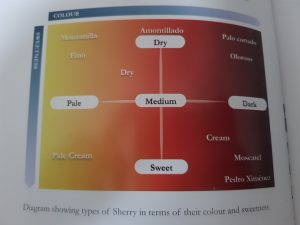

I also think that people just don’t understand it. We most often think of it as being sweet, which is certainly true for some. However, there is a whole world of styles out there… dry, mid-dry semi-sweet, etc. etc., but we will come back to this.

How is apera made?

After primary fermentation of the base wine, apera is fortified (simply meaning to “add spirits to wine”). Because the fortification takes place after fermentation, most sherries are initially dry, with any sweetness being added later.

What makes apera so unique is the use of flor yeast. After standard white winemaking procedures, the wines are transferred into barrels, which are only partly filled. The wine in each barrel is then seeded with a special yeast (flor yeast) and stored for several years. Because the barrels are only partly filled, the wine’s upper surface is exposed to air – providing ideal growing conditions for the flor yeast. As the yeast grows it forms a film across the surface.

The solera system

Another unique feature in the production of apera is the use of a solera system. Barrels of wine are arranged in a pyramid-like stack with the youngest wine in the top layer and the oldest wine in the bottom layer. At bottling time, the wine to be bottled is removed from barrels in the bottom layer of the solera, taking only a small portion. Then each cask is refreshed from the layer above. This results in a progressive mixing of young wine with older wine, a process known as ‘refreshing the wine’.

Another unique feature in the production of apera is the use of a solera system. Barrels of wine are arranged in a pyramid-like stack with the youngest wine in the top layer and the oldest wine in the bottom layer. At bottling time, the wine to be bottled is removed from barrels in the bottom layer of the solera, taking only a small portion. Then each cask is refreshed from the layer above. This results in a progressive mixing of young wine with older wine, a process known as ‘refreshing the wine’.

Styles

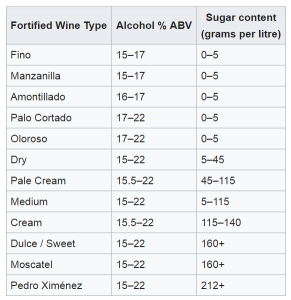

Apera comes in a variety of styles… most of which we also can’t mention for locally made versions! For your information though, there are a couple of useful tables to describe the varieties of Spanish sherries below…

To try some of these varieties side by side (and to understand how they can be paired with food), Seppeltsfield in the Barossa offers a great tasting.

If you’re wondering what the dry end of the apera spectrum tastes like (just between us, it’s in the palo cortado style – but don’t tell anyone I said that), why not pop in to see us and we can pour you a little of ours – it’s a great aperitif!

You didn’t know Rob made a Somerled apera?!

Well, you do now! …and it’s for sale through the cellar bar.

Tell us a bit about your apera Rob…

“The apera that we have in a barrel, and a few bottles, was made in the SA Riverland from the 2009 vintage. It was made from palomino grapes, the grape variety that most Spanish sherries are made from. In my early days of winemaking, there were many growers across the country who grew palomino and they usually grew pedro ximenez as well. In those days fortified wines were much more popular than now, so over the years some really nice palomino vineyards have been removed as no one wanted the fruit.

“Palomino produces a rather neutral dry white wine, nowhere near as aromatic or flavoursome as riesling or sauvignon blanc for example. This is one of the reasons that palomino dry white makes such a good base for the most delicate, pale dry apera wines. But it also makes a great base for the more robust, deeper coloured aperas.

How did you make it…

“So our apera started off as a delicate dry white, very pale, and was fortified with very neutral grape spirit to an alcohol content of 15%. It was clarified and pumped into barrels that had been used for wine storage for some years previously. The barrels weren’t fully topped, as is usual with table wines, but were filled to about 75-80% full, leaving quite a headspace above the wine. On to the surface of the wine, a specially selected yeast, called a flor yeast, was gently sprayed. This yeast is one that will grow on the surface of the wine, unlike the usual wine yeast which grows all through the juice/wine. The wine is quite dry (ie contains no, or almost no sugar), so there’s none of the usual bubbly fermentation, but instead the flor yeast spreads across the wine’s surface. It produces a compound called acetaldehyde, and this is what gives the apera its typical aroma and flavour. It helps to protect the wine against oxidation, and that’s why the apera stays so pale while the flor yeast continues to grow.

“We were fortunate enough to be able to purchase a couple of barrels of the young apera in 2011, and some of you may remember seeing the apera in a glass-headed barrel that we kept in the cellar door for some years. That barrel is still our main apera barrel, but is “kept out the back”..!

And what about that “work” trip to Spain?

“As the apera developed, it became more and more difficult to maintain the flor yeast film on the surface, so the colour of the wine started to deepen. It so happened that Heather and I spent a month in Spain about then, and much of that time was spent in the south of Spain, particularly in Jerez which is often said to be the capital of the Spanish sherry industry. We visited some wonderful bodegas and even though I started off with a high degree of scepticism, I/we were won over by the range and variety and absolute quality of the sherries. One wine style that we loved enormously was the very old Palo Cortados which were a lovely golden tawny colour, dry as a chip, and with wonderfully complex aromas and flavours. A similar style in Australia would be an aged apera that we used to call Amontillado, but the Australian version of an Amontillado always had a fair bit of residual sugar.

“So, I could immediately see a great future for our Somerled apera as a wine modelled on the Spanish Palo Cortado style – and that’s the way it’s going. It’s now over 9 years old, and has been in barrel for nearly all that time. The flor yeast film has long disappeared, but the flor influence is still there, just as it is in the old Spanish Palo Cortados. It has deepened further in colour, so that it has a lovely golden tint with a touch of the tawny, and the aromas and flavours are incredibly lifted.

“So, I could immediately see a great future for our Somerled apera as a wine modelled on the Spanish Palo Cortado style – and that’s the way it’s going. It’s now over 9 years old, and has been in barrel for nearly all that time. The flor yeast film has long disappeared, but the flor influence is still there, just as it is in the old Spanish Palo Cortados. It has deepened further in colour, so that it has a lovely golden tint with a touch of the tawny, and the aromas and flavours are incredibly lifted.

“The Somerled apera has an alcohol of just on 15%, so it’s not much more than a big red table wine, and this helps the wine to remain soft. It doesn’t have the bite of a lot of other aperas which are closer to 18%”.

Has this post piqued your interest in apera?

Why not pop in this weekend to try some for yourself!

Not in Adelaide? That’s ok… we can ship a bottle (or two!) to you anywhere in Australia!

Brilliant telling of the sherry story !

Perhaps a little biased, but thanks!